From Wild To Menagerie

As in other urban parks, patrons donated animals to be displayed in cages in Central Park. Donated animals came from near and far, connecting the park to ecosystems undergoing rapid change due in part to the activities of companies connected financially with New York City.

Architects Olmsted and Vaux neither planned for nor desired to build a zoological garden in the park. They believed that a zoo would detract from the park’s carefully designed sight lines. However, upper- and middle-class New Yorkers believed that a zoological garden was essential for New York to match the cultural, scientific, and educational achievements of European cities. Olmsted and Vaux soon conceded that a caged animal collection was inevitable, and Olmsted (amid a bout of melancholy) went on a tour of zoological gardens in Brussels, London, and Dublin. Over the park’s first four decades, park officials tried numerous times to establish a zoo in different locations, but they had little support from scientific societies. Donors gave a rather random assortment of animals, which leaders did not consider educational or scientific.

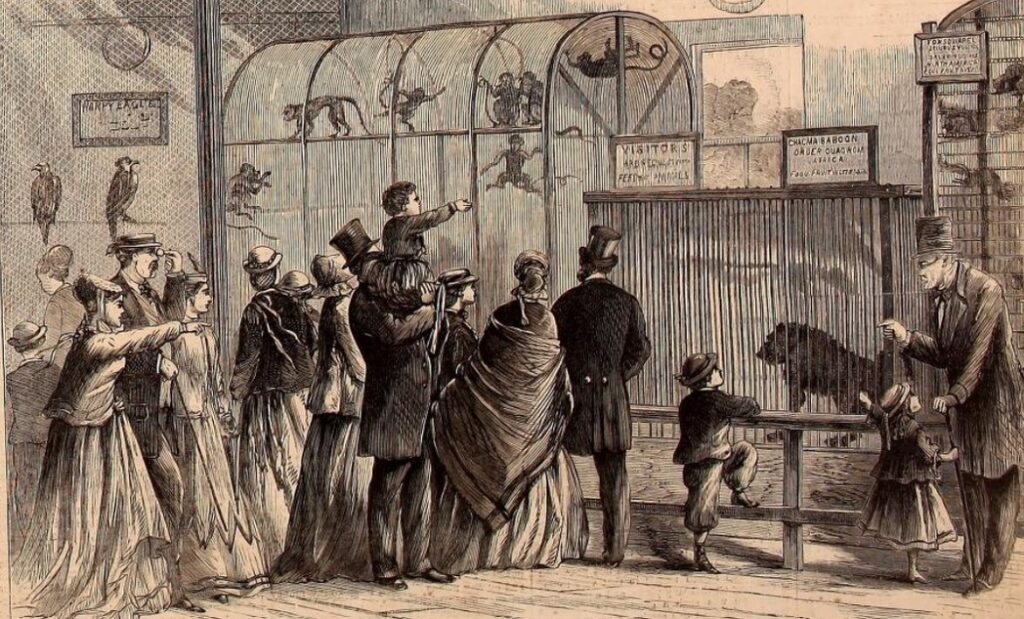

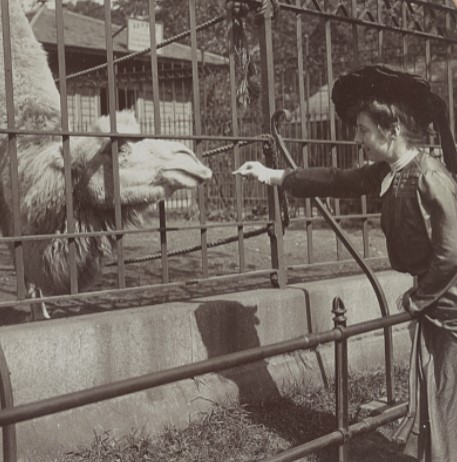

The exhibit was called the “menagerie,” a term considered inferior to “zoological garden.” In spite of its inferior title and the way it clashed with the park landscape, the free menagerie attracted a huge following of New Yorkers; some park leaders claimed that it drew the largest crowds in all of Manhattan, including many working-class and immigrant residents.

All kinds of people donated animals to the menagerie for all kinds of reasons, but many reasons had to do with the way urban growth affected spaces for creatures in and around the city. Residents of nearby neighborhoods and towns donated pets they could no longer manage in small residential spaces. For example, from 20 blocks south of the park on Broadway, the O’Shea family donated guinea fowl, guinea pigs, and a “yellow bird.” Other families even donated pet monkeys or alligators acquired as souvenirs as babies (Teddy Roosevelt donated an alligator at age 15). As urban apartments became smaller, and private yards disappeared, families probably determined that pets were too hard to keep.

Others donated wild animals (some of them injured) that they happened to encounter and capture. A man gave a wading bird called a rail who had collided with a window. The manager of the Fulton Fish Market contacted zoological director William Conklin when fishermen accidentally caught sea turtles. Individuals dropped off rabbits, raccoons, and even deer at the menagerie, animals caught as the city converted habitat to pavement and buildings. A business association gifted bald eagles captured on Long Island.

Park comptroller Andrew Haswell Green believed that a zoological garden could educate New Yorkers (especially city children and immigrants) in natural history, to help them appreciate species and environments of the American continent. Green was particularly concerned about animal species that were dwindling toward extinction as the American empire pushed west. Business, government, and military leaders sent animal specimens from western locations, but ironically many donors also contributed to the decline of ecosystems and Indigenous life in which these species played important roles.

Most notably, the Seventh Cavalry sent a buffalo from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in 1868. This military unit, which included General George Custer, also waged war on Kiowa, Comanche, Pawnee, and other Indigenous groups, and helped separate tribes from buffalo whom they considered kin. The Seventh Cavalry defended settlers who brought domesticated cattle to the Plains, replacing buffalo. They also protected railroads that divided the Plains and transported buffalo hides to industrial centers in the east, where they were used as belts to turn gears in factories.Other businessmen, in industries from the fur trade to railroads, donated bears and pronghorn antelope from out west. Railroad financier Thomas Durant donated a grizzly bear from the Pecos River. Profits from the US’s industrial growth helped build investors’ wealth in New York, the center of American finance. These profits in turn fueled the kind of urban expansion that encroached on local wildlife habitats.

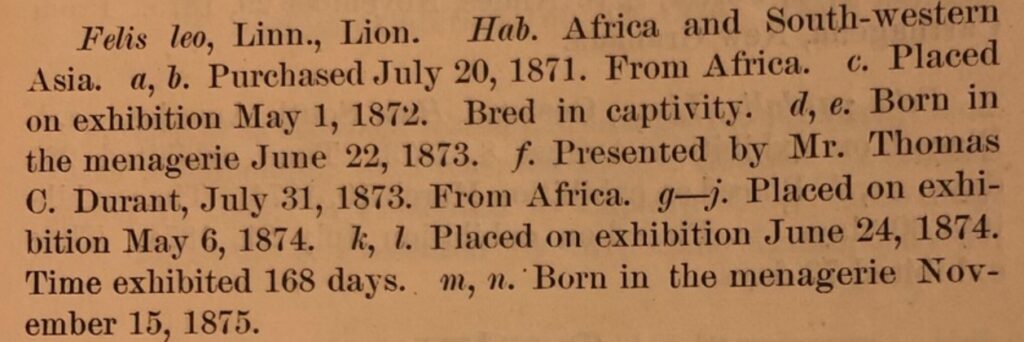

The park’s zoological director William Conklin also secured donations and loans of larger, more exotic animals. Showman P. T. Barnum left elephants, lions, camels, and other large animals in the menagerie’s care during his circus’s off-season. Conklin also worked with the Philadelphia Zoo to bring a greater variety of animals to audiences in New York. Fur traders gave extra animals caught to the menagerie, such as Syrian gazelles and musk deer. Conklin worked with leading animal traders such as Louis Ruhe and Charles Reiche & Brothers to borrow animals that enlivened the collection. Some large, charismatic animals were donated, such as a lion from railroad financier Thomas Durant; the lion’s origin is listed only as “Africa.” Some animals were bred in the menagerie, which Conklin considered a sign that the animals were healthy and well-adjusted to captivity.

Interested in learning more? Check out these resources.

Animating Central Park chapters 3 and 5

Daniel Bender, The Animal Game: Searching for Wildness at the American Zoo. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016.

Katherine Grier, Pets in America. A History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Elizabeth Hanson, Animal Attractions. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Andrew Isenberg, The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History, 1750–1920. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Harriet Ritvo, Noble Cows and Hybrid Zebras: Essays on Animals and History. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010.