Urban Waters

Architects and workers created new water bodies in the park that officials, donors, and visitors stocked with fish. Amid the park’s first several decades, development buried and paved over many of Manhattan’s historic waterways. New Yorkers who still wanted to fish increasingly found recreation, food, and connection to nature in the park’s waters.

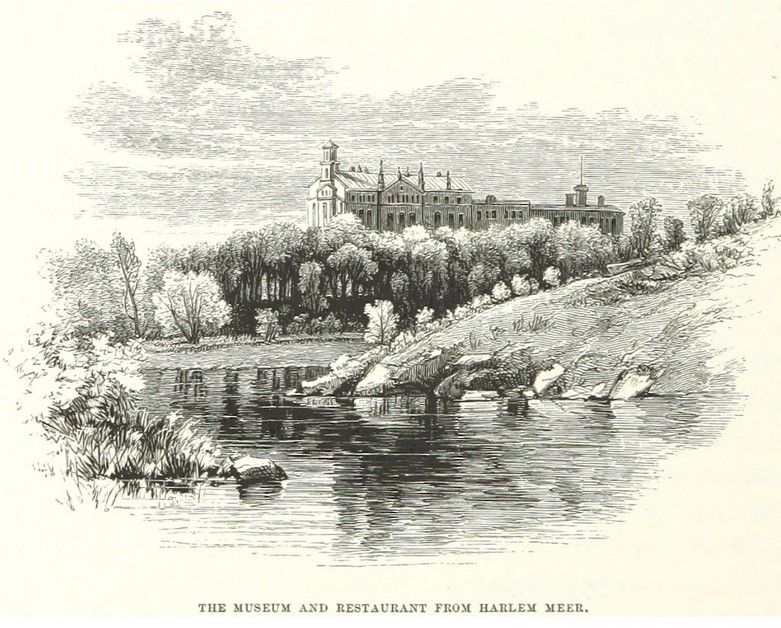

Architects, engineers, and laborers reordered Manhattan’s drainage and aquatic landscapes as they built Central Park’s water bodies. The original receiving reservoir was completed in 1842 to contain water that flowed in from the Croton Dam in Westchester County. The upper reservoir was constructed in tandem with the rest of the park in the 1850s and 60s. Workers also built the Lake, the Harlem Meer, and other streams, pools, and ponds. A system of pipes that ran below the park’s grounds and waters sustained these water bodies. Water and aquatic life–from rotifers, mollusks, and crustaceans to small fish and even cholera bacteria–flowed into the park from the rest of Manhattan.

Some New York State officials tried to promote fishing and fish culture in the park. Leading Democratic politician (and future governor) Samuel Tilden donated 568 trout in 1869. State Fisheries Commissioner Robert Roosevelt (uncle of future president Theodore Roosevelt) urged the development of aquaculture facilities, but his recommendation never came to fruition. Other New Yorkers worried that the water bodies were unhealthy and debated whether fish were part of the problem or part of the solution.

Regulating and enjoying urban waters

No person shall bathe, or fish in, or go, or send any animal into any of the waters of the Park, nor disturb any of the fish, water-fowl or other birds in the Park, nor throw or place any article of thing in said waters.

Central Park Ordinances, section 22

By the 1860s, park ordinances section 22 barred visitors from fishing or placing anything in the water bodies. This rule was especially important for protecting the city’s water supply, held in the two reservoirs. However, fishing had long been an important way for people in rural and urban places to obtain food and connect with other life. The names of the regular folks who surreptitiously stocked the park’s waters are lost to history, but they surely did release goldfish, catfish, perch, and other species.

As the city grew around the park, fishers mourned the burial of streams and ponds under pavement. One Harlem old-timer remembered a popular fishing spot known as “goldfish pond.” Migrants from the US South, the Caribbean (including Puerto Rico), and Italy brought rural fishing traditions to the city. Children and youth from Harlem fished in the Harlem Meer and other water bodies at the park’s north end. Park police often chased them in their efforts to enforce rules against fishing. Adults also fished for food and recreation in the park; if caught, they might be fined a dollar. The park rescinded the rule against fishing in 1948.

Draining the Reservoir

In 1930, after decades of concerns about the need for more space for human activities in the park, city officials drained the original receiving reservoir. The Southern New York Fish and Game Commission helped truck some 10,000 fish–including bass, perch, sunfish, and several enormous eels–to “new abodes in reservoirs and lakes of Westchester County” where they could be admired and caught by anglers. Throughout the 20th century, local companies also introduced new fish into Central Park water bodies, and sporting and environmental organizations encouraged children to learn to fish as a way of connecting them with non-human life.

Interested in learning more? Check out these resources:

Animating Central Park, chapters 2 and 6.

Sergey Kadinsky, Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide. Countryman Press, 2016.

Kara Schlichting, New York Recentered: Building the Metropolis from the Shore. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Ted Steinberg, Gotham Unbound: The Ecological History of Greater New York. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2014.