Introducing Birds

Park leaders and some naturalists were eager to “animate” Central Park – to use animals to make the landscape lively and appealing to city-dwellers, and sometimes to control insects. Donors worked with park leaders to introduce birds associated with storied landscapes abroad.

Central Park supporters believed the park would help elevate New York’s status as a world city on par with European cities with grand parks, and elegant swans were part of that aesthetic. In 1860, the government of Hamburg in the German Confederation shipped 12 swans from its bevy on Alster Lake, which the city had maintained since the 1600s. The local culture there considered swans good luck, so long as they were respected. Meanwhile, in England, two traditional livery companies together donated 25 breeding pairs of swans to Central Park. (In England, all swans belong to the Crown, except those allotted to these two companies through a ceremony called swan-upping that dates back centuries.)

Park officials released the swans on the Lake, pinioning their wings to prevent escape and building concealed nest boxes, as directed by swan-keepers in Hamburg. Art critics and media hyped the swans’ graceful bearing in the landscape, and visitors sought out contact with them from rustic landings along the lake’s shore, offering bread and cake. The swans also ate fish eggs and aquatic vegetation, shaping the Lake’s ecology.

Meanwhile, outbreaks of spanworms worried park officials, along with farmers and horticulturists across the US. These inchworm relatives devoured foliage of orchard and ornamental trees, and often dropped onto horrified park visitors. The acclimatization movement, which originated with European naturalists studying animals across empires, promoted the importation of foreign animals as a scientific, economic, and cultural endeavor. Many acclimatizers recommended the European house sparrow to help control spanworms and also to enliven urban landscapes. Eugene Schieffelin, an amateur naturalist and later an officer in New York’s Acclimatization Society, began releasing house sparrows at his family’s Madison Square estate in 1860. Later, Schieffelin worked with zoological director William Conklin to release more European birds in Central Park. House sparrows adapted easily to urbanized environments and farms. As they proliferated, naturalists hotly debated their effects on native birds and ecologies – a debate known as the “Sparrow Wars.”

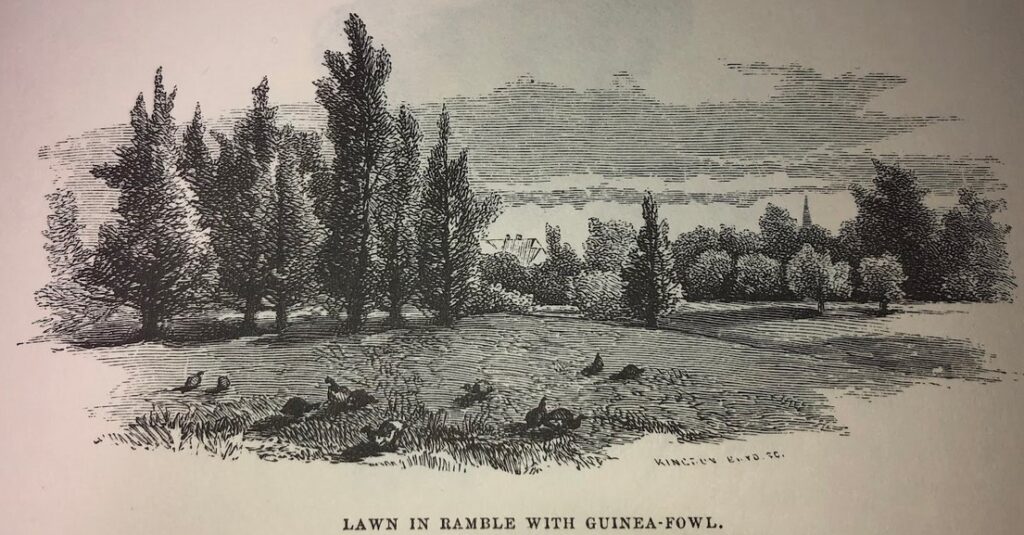

Conklin felt strongly that house sparrows made the landscape more lively. In his role as park zoological director, he pursued further partnership with the Acclimatization Society. Members released species such as skylarks, “English” pheasants (they actually originated east of the Black Sea), chaffinches, and starlings through the 1870s and 80s. Amid a craze for guinea fowl among gentlemen farmers, Conklin and other donors also released these birds into the park. Agricultural communities across sub-Saharan Africa had domesticated guinea fowl; enslaved people had brought them to the Americas on slave ships. Now a small flock ranged throughout the park, gobbling insects.

Eugene Schieffelin first released starlings in the park in 1876, but these dispersed to New Jersey and attracted little notice. He released 80 more in March of 1890, and these stayed in the park, multiplied, and spread. There is no evidence from Schieffelin’s lifetime to support the claim that he was trying to introduce all the birds from Shakespeare’s plays. Stories about Shakespearean motivations for acclimatization originated a few decades later. Today, bold, adaptable house sparrows and starlings remain some of the most common birds in US cities.

Interested in learning more? Check out these resources.

Animating Central Park, chapter 2

Peter Coates. American Perceptions of Immigrant and Invasive Species Strangers on the Land. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

Harriet Ritvo. Noble Cows and Hybrid Zebras. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010.

Thomas Dunlap, Nature and the English Diaspora: Environment and History in the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Pete Minard. All Things Harmless, Useful, and Ornamental: Environmental Transformation through Species Acclimatization, from Colonial Australia to the World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.