City Farmland

In the 1850s and 60s, public health regulations and New York’s development restricted urban livestock agriculture. Meanwhile, officials introduced sheep into the park to represent iconic farming landscapes. New lambs’ purebred pedigrees traced back to the origins of the Southdown breed in Southeastern England.

English sheep for an urban American park

Gentlemen farmers throughout the northeastern US believed that elite European livestock breeds and modern science would help improve animal husbandry in America. As a young man, park co-architect Frederick Law Olmsted had apprenticed with George Geddes, an engineer who raised sheep and also served as a New York State Senator. Park Comptroller Andrew Haswell Green had experience raising sheep and cows on his family farm in Massachusetts. Olmsted and Green both valued the farming landscapes of England and the rural northeast, for their effects “on the taste of a community—and through that on their hearts and lives.”

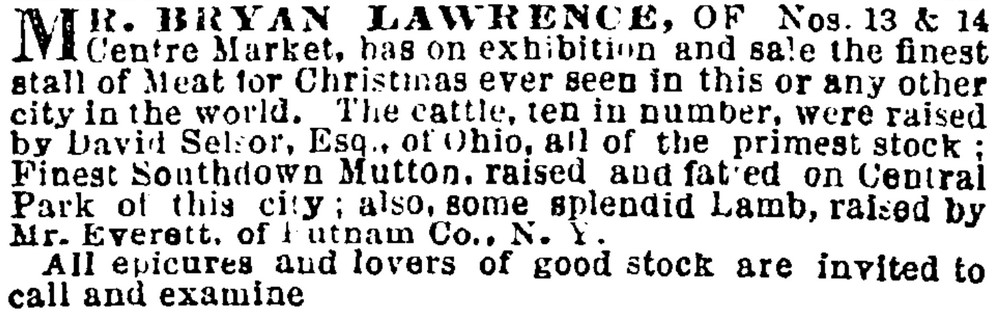

As city health officials regulated livestock and the park pushed out agriculturalists, Olmsted, architectural partner Calvert Vaux, Green, and other leaders envisioned a city-owned and -managed farm in the park. Their vision differed from town grazing commons, like Boston once had. Park leaders believed that a flock of sheep and a working dairy could expose city folks to iconic pastoral landscapes, promote scientific animal husbandry, and earn revenue to offset the park’s construction costs. In 1862, park administrators began purchasing Southdown lambs from Bryan Lawrence. A high-end butcher, Lawrence may have bought them from Samuel Thorne’s farm in Millbrook, NY. Thorne obtained his sheep from the legendary English breeder Jonas Webb.

“High” farmers and consumers valued livestock in part for their geographic origins, like the terroir of fine wines. Gentlemen farmers and discerning consumers in the US revered Southdown sheep for their mutton, and for their storied geographic origins in southeast England. Bryan Lawrence sold Central Park mutton at Centre Market downtown. A shepherd and his family, along with a sheepdog, lived with Central Park’s flock in the sheepfold building. Shepherd and dog guided the flock around the park meadows throughout the day, where sheep converted grass into flesh, fleece, and rich manure. At its peak, Central Park’s flock numbered over one hundred, and farmers and butchers from around the region attended the park’s sheep auction each June. The auctions had an elite flavor, but New Yorkers of all classes and ages seemed to delight in the sheep.

Healthy milk for the city?

Vaux and Olmsted, inspired by London’s St. James’s Park, also planned a dairy building where mothers and nannies could purchase treats made from milk from cows who would live in a ground-level barn below the serving area. (In St. James’s Park, milkmaids brought cows in from suburban farms and charged a penny for a cup of milk fresh from the cow.) Tainted cow milk killed hundreds of city infants. Olmsted and Vaux promised the Dairy would provide pure, healthy fare. Andrew Green donated some cattle from his family farm in Massachusetts, and the park received other bovine donations. However, a new park administration in 1870 converted the dairy’s cow quarters to storage space, and the upper floor to a generic snack bar

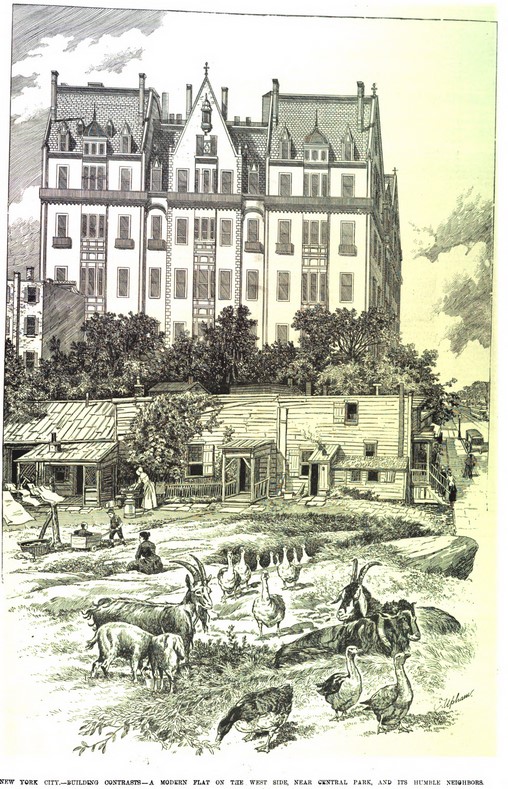

The persistence of goats – and farming families

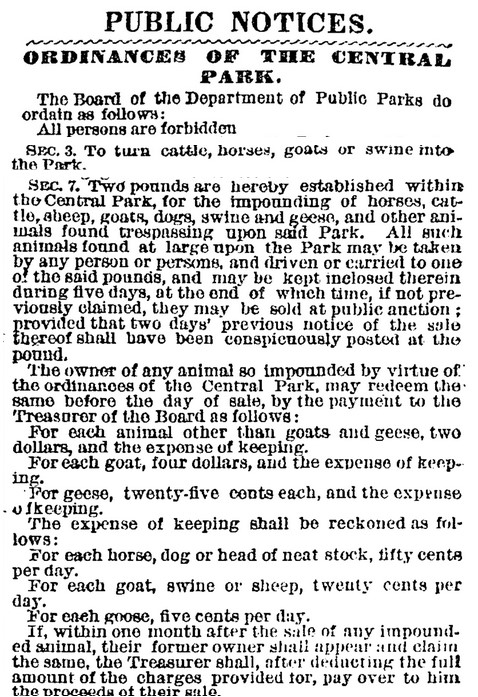

Meanwhile, through the 1870s, goats belonging to farming families outside the park (including some who once lived there) continued to wander into the park. The goats browsed on new plantings; Olmsted warned that vegetation would not thrive while they ran at large. He later remembered that “the whole place was infested with goats.”

As public health regulations cracked down on some livestock in the city, and development around the park pushed animal agriculture into marginal and less-visible spaces, park officials maintained a romantic picture of northeastern farms with its sheep and cow displays. At the same time, the rural spaces represented by these displays were disappearing. Small sheep farms in the Northeast dwindled, eclipsed by larger ranches in westward-spreading territories.

Interested in learning more? Check out these resources:

Animating Central Park, chapter 1

Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and Theodora Kimball, Forty Years of Landscape Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1973 [original 1928].

Mike Rawson, Eden on the Charles: The Making of Boston. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Frederick Brown, The City Is More Than Human: An Animal History of Seattle. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016.