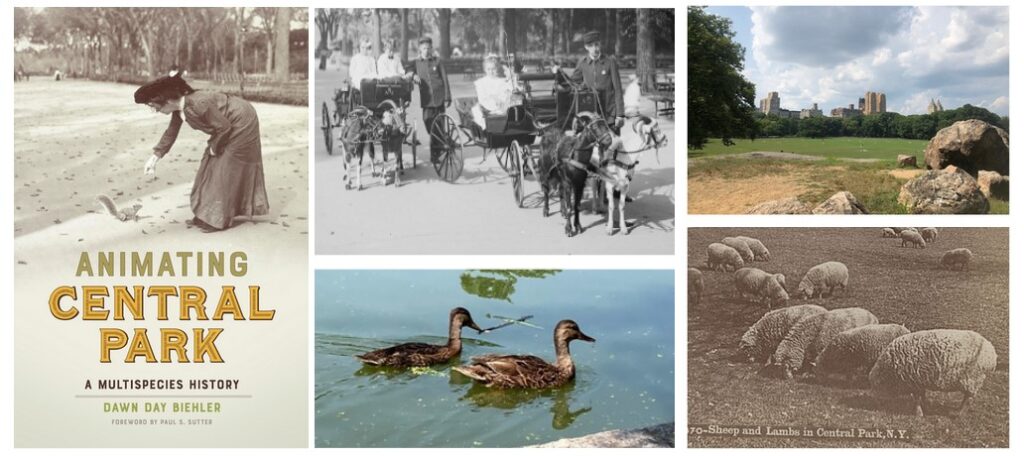

Animating Central Park: A Multispecies History

Complicated oases

Imagine yourself visiting an urban park — maybe New York City’s Central Park, Washington, DC’s Rock Creek Park, or Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park. Most of us enjoy urban parks as havens from the pavement, crowds, and noisy bustle of the blocks beyond. The point of going to the park is to escape from the “concrete jungle” into a protected green oasis.

However, a deeper exploration of urban parks and their history reveals how entangled green spaces are with the way cities grow. New York City’s growth was fueled by trade, industry, and investment. Companies trading and manufacturing goods transformed spaces in the city for ports, factories, warehouses, and offices. They also extracted resources from more distant ecosystems and communities.

Real estate interests bought up land to develop for profit, including housing: from mansions for elites to tenements for laboring classes. Elites who promoted Central Park included people who made their fortunes through these activities. They demanded that some space be designated as park land amid the growth. Land selected for the park was not simply “natural” – people made communities and livelihoods there.

Animals, parks, and urban growth

Since Central Park’s early days, animals have made important connections between the park and other urban spaces, along with more distant locations. Urban growth always transforms animals’ lives and the lives of the humans with whom they are interdependent. The creation of Central Park displaced some human-animal relationships and made new spaces for New Yorkers of many classes and identities to encounter animals.

Many New York reformers were concerned about the loss of country landscapes and wild ecosystems, near and far. They saw the park as a place to display agricultural animals and representatives of threatened species. Meanwhile, however, urban elites’ companies and investments put pressure on farms and habitats where many animals lived.

Central Park’s multispecies history has much to teach us about urban green spaces and human-animal relationships. As in the nineteenth century, when many city parks were established, people today are also eager to create urban green spaces. Examining the power dynamics of human-animal spaces in early Central Park can help us recognize continued threats to ecosystems, wildlife, and farms. It can also help us envision cities’ possible role in supporting animals.

Exploring Central Park’s animal connections

This web site invites readers to explore the stories and movements of animals, and their relationships with humans, in the early days of Central Park. The maps here show just a few examples of how human-animal relationships connected distant spaces with the park. The site is a companion to the book Animating Central Park: A Multispecies History by Dawn Day Biehler.

A note on language

It is difficult to find the right language for describing the diversity of life without creating categories that are too simple or exclusive. Humans are animals, but when we say “animal” we are often referring only to non-humans. This site uses “multispecies” to refer to groupings of more than one kind of life, including humans, and “more-than-human” refers to the way non-human animals can still alter and affect a world dominated by humans.